|

Part Six

Just as General Roosevelt

had stated, about two weeks after meeting him on Utah Beach I was told to

report to the 4th Infantry Headquarters, where I received my next

assignment. I know the soldiers in C Company must have wondered what was

going on with me, especially since one of their sergeants was ordered to

drive me to 4th Infantry Headquarters in a command car.

All this time, it was my

choice to wear the stripe of a private first class. When I arrived at

Headquarters, I was given my assignment and told that I had been given a

field commission with the rank of major. I told them I didn’t want the

commission, but finally agreed to the rank of staff sergeant, my reason

being that, were I to be captured, my interrogation would be less severe if

I were a sergeant than if I were a major.

While I was given my staff

sergeant stripes at that meeting, I did not sew them on to my uniform until

several months later, and I still had a very hard time explaining this

sudden promotion in rank to the other men in C Company. Although most of

them knew I was doing something connected with G2, they thought it better

not to question me about it—and of course they knew I wouldn’t tell them

anything, anyway.

There was another reason,

though, why they more or less accepted my promotion, as well as the special

attention given to me by the officers (who only guessed what I might be

doing, but who also really did not know). Several months earlier, a soldier

who was about five inches taller and fifty pounds heavier than me thought he

was entitled to know exactly what was going on and why I was gone so much of

the time. When I told him it was really none of his damn business, he

decided he was going to beat the information out of me. He directed several

punches in my direction and found himself flat on his back each time. He

finally decided maybe it wasn’t really necessary that he know what was going

on.

I did form some close

friends with the men in the C Company motor pool, with whom I usually rode

when I was not on assignment. When I didn’t show up when C Company moved

out, they figured I had bummed a ride on one of the tanks or in one of the

company’s jeeps or, as usual, had just disappeared.

During the period from D-Day

to the end of my first mission after landing on the continent, I lived

partly on C-rations, which consisted of canned meats and vegetables packed

in preservatives, along with hard biscuits. But mostly I lived on D-rations,

a chocolate camouflaged candy bar. It was supposed to have all the nutrients

needed to live, and it took up very little space. I did manage to shoot a

deer and a squirrel during that time, and I cooked both over an open fire

until they were done well enough to eat. I also managed to catch some fish

by throwing a hand grenade into a stream and grabbing the fish, stunned by

the concussion, as they floated to the top. This method of survival lasted

for a period of about six weeks, initially because the 42nd’s kitchen had

not caught up with us as fast as they thought it would, but primarily

because I left to go on my mission. When I finally got back to an area where

they had an army kitchen serving real food, the first bite of army bread

tasted so good it was like eating a piece of delicious cake.

For the most part, my

missions consisted of the elimination of SS Officers, Gestapo agents and

other targets. While I was in France or Belgium, this was to be accomplished

in a manner that would not put blame on the population. While in Germany or

with German troops, I was to try, if at all possible, to make it look as if

the targets had been killed by one of their own men. In some instances I

managed this by patiently waiting until the targeted officer or agent

“dressed down” one of their underlings. This most always seemed to happen,

and when it didn’t I would try to find a way to make it happen. I would then

play up the incident by saying, “Did you see that?” or “Did you hear that?”

to others who were in the area and under the command of the target. When the

target was eliminated, these men, who hoped their cooperation would advance

their military careers, would relate what they had heard or seen to those

investigating the killing, implicating the individual I had set up. In order

to make their accusations even more believable, I would sometimes switch the

gun of the scolded soldier with mine, use his gun to eliminate the target,

and then switch the guns back again. I would evacuate the area as soon as

possible after eliminating the target, so I was usually not around to see

the repercussions of my actions. Of course, the above did not always work

out, and in those cases I eliminated my target and managed to escape in the

confusion.

While on most of my

missions, I would try to arrange for one or two changes of either civilian

clothing or German uniforms. I would keep these in my contact’s home or some

other place where they would not raise suspicion, should German soldiers or

the Gestapo accidentally find them. Sometimes a change in clothing and

appearance would work to my advantage when I was trying to leave an area.

When I eliminated a target,

it wasn’t like the shoot-outs in the movie, High Noon or on the TV

show, Gunsmoke. I did my very best not to attract any attention, and

to make certain that women—and especially children—were not around. In many

instances, my target never even knew what hit him.

I was lucky enough to be

with the 4th when they made their way into Paris on August 25, 1944. I was

told we could have arrived earlier, but that we had to wait so that Charles

DeGaulle and his “Fighting Free French Forces” could be the first Allied

armed forces to enter Paris. At first we were all looking for German

snipers, who we thought would be hiding out in various buildings, but I

didn’t encounter a single one. And the Parisians must have known that the

Germans had all fled, as thousands of them lined the streets cheering,

waving and trying to grab and hug any American soldier they could reach. It

was a great feeling.

I was invited by a lovely

young lady, whose name was Yvonne, to come to the home of her parents and

have supper with them. Her dad dug out some dust-covered bottles of

champagne that he had been hiding just for that occasion. I brought some

canned Spam, beans and other food I was able to talk the mess sergeant out

of, and all in all, we had a very enjoyable and happy meal. I know that they

lived across from a park named the Bois de Vincennes, but when my wife and I

returned to Paris in 1953, I was unable to locate them.

After leaving Paris, I

received orders for another mission in Germany. I was in a German uniform

and, having just eliminated my target, thought everything had gone well,

when four uniformed German officers surrounded me. I was certain this was

going to be my final mission, and that the four officers would try to take

me alive for questioning, and then have me hung or shot.

I made up my mind to make a

break for freedom, and in the fight that followed I was stabbed in the meaty

part of my left palm. I knew I had been stabbed, but I felt no pain. I

remember blinding one of my assailants by squirting blood from my hand into

his eyes. Somehow, after what seemed like an eternity but was, in all

probability, only a minute or two, I was the only one left standing. I made

certain they were all dead and, after hastily stopping the bleeding from my

hand and putting myself in as presentable a condition as possible so as not

to attract any more attention, I grabbed the hunting knife with which I had

been stabbed and left the area as fast as my bruised body would take me. I

still have a scar on the palm of my left hand to remind me of this incident,

as well as the hunting knife.

After I was debriefed on

this mission, it was reviewed by General Smith—something that did not always

happen—and I was called into his office. The General complemented me on a

“great mission,” and then added, “Hammerman, you never know when to give up,

and in your case that’s an exceptional quality.” I replied, “General, that’s

the way your people trained me.”

After all these years, I

still find it difficult to talk or write about some of the missions. This is

partly due to the fact that in each of my missions, whether or not I was

successful in the elimination of my assigned target, I did eliminate a

number of other people, almost all of whom were either Gestapo or SS

officers, and, yes, a few civilians. In early October of 1944, for instance,

I was assigned to eliminate the SS officer in charge of an SS Panzer

division defending Aachen. I was flown in a captured German transport plane

to an airfield near Dortmund. Exactly how that was accomplished, I don’t

know. I do know that the pilot spoke better German than I did, and seemed to

say all the correct things to get permission to land and permission to take

off again after I deplaned.

I had papers identifying me

as an SS officer who had sufficiently recuperated from wounds received on

the Russian front, and who was being reassigned to the SS Panzer division. I

knew these papers would only be good until I got to Aachen, and I was

fortunate to run into an SS officer who was also being transferred to the

Panzer division there. He was about my height and weight, and we struck up a

conversation while sitting next to each other on the transport vehicle

taking us there. I inquired as to why he was being transferred and whether

or not he knew anyone at Aachen. He told me he knew no one in the unit, and

this is what I had hoped for.

At a stop along the way, I

eliminated him and took his identification papers. I reported to the SS

Panzer division and was lucky enough to be temporally assigned to the

headquarter company where my target was in charge. I had been there eight

days when I was told to report to headquarters, which was in a bunker or

pillbox that was part of the Siegfried Line. I wondered why my presence was

being requested and worried that I had been discovered.

The division was under heavy

attack by American artillery and air power, which was providing cover for

the approaching Allied infantry. The infantry was going to try to knock out

the pillboxes, since neither the artillery shells nor the bombs being

dropped seemed to have any effect on them. While the artillery and machine

gun fire did help to conceal what I was about to do, it also scared the

living daylights out of me. It was as if all hell had broken loose, and I

thought every shell that whistled in was aimed right at me.

I made my way to the bunker

and used two hand grenades to eliminate everyone inside. The Germans thought

this was the work of the American infantry unit, who they assumed had

managed to infiltrate the area. The American artillery fire did indeed

injure me, and though the injury was minor, it was very bloody. This gave me

an excuse to leave the area to seek medical attention.

I know that what I did

during these missions makes me look like a cold-blooded killer, and I guess

I was at the time. But the fact is that I was one person during the war, and

a completely different person when I came back home. If I had the slightest

inkling that someone suspected me, I got rid of him or her. One time I

thought an SS officer’s aid suspected me because he was looking in my

direction as he was pulling his P38 automatic. I shot the aid before he

could fire or say anything. I then told the SS officer that it looked like

his aid had pulled his gun and was going to kill him, but that I was able to

shoot him before he could fire his weapon. The SS officer was grateful, but

still suspicious. I got out of there at the first opportunity, and never did

eliminate my original target.

I caught up with the 4th

Infantry Division in early December of 1944, when they were dug in and

fighting in the Hurtgen Forest, located on the German/Belgium border just

south of Aachen. I first stopped by Division Headquarters to see if any new

orders had been sent for me, and to let them know that I would again be

temporarily joining the 42nd Field Artillery. I also picked up my mail, and

a package which had taken eleven weeks to catch up with me. In the package

there were two bottles of Coke. They were only six-ounce bottles in those

days—Pepsi didn’t introduce the twelve-ounce bottle until sometime after the

war. There was also a two-pound kosher salami that was covered with mold.

I was standing by a

maintenance truck when I opened the package, and the five soldiers who

manned the truck were watching me and drooling. One of them offered to pay

me $5.00 for one bottle of Coke. I refused his offer, but immediately peeled

the skin and mold off the salami and cut it into six pieces, and poured out

six equal portions of Coke into each of our canteens—all of which we quickly

consumed.

The Hurtgen Forest was a

dense forest of pine trees, and the German artillery had zeroed in on the

American troops dug in there. Their artillery shells would hit the trees,

explode, and rain shrapnel down on the American troops below. Foxholes

initially offered no protection, so the GIs cut down trees, being very

careful to camouflage the exposed trunks to avoid having their position

detected by spotter planes. They covered each foxhole with cut sections of

tree, piled dirt on top of the logs, and used tree branches to camouflage

the dirt and to cover the floor of the foxhole.

The tank and vehicle

maintenance group with whom I had shared the salami and Coke dug a hole six

feet wide by six feet long by five feet deep, which the six of us shared—two

men doing a two hour guard duty while the other four tried to sleep. I spent

a week in that foxhole undergoing some of the heaviest artillery fire of the

war. I later learned that a German officer who had previously been on the

Russian front indicated that the fighting in Hurtgen Forest was fiercer than

any he had been involved in.

After achieving their

objectives, the 4th received orders to transfer from the Hurtgen Forest to

the Battle of the Bulge. We left at once to relieve the surrounded troops

there, and made an overnight march under blackout orders. The next morning

we passed Malmedy, where eighty-four captured American soldiers had been

shot to death because the enemy officers didn’t want to take the time to

process them as prisoners. Their helmets were all stacked on the side of the

road, and all of the men from the 4th gripped their guns and just looked at

the helmets without saying a word. They didn’t have to; I knew what they

were thinking, and I was having the same thoughts.

We left Malmedy and headed

for Luxembourg, where we ran into heavy artillery and tank fire. Our company

took refuge in an old castle with very thick walls, which made it a good

buffer against the heavy German artillery fire. Some of our soldiers found a

storage vault in the lower part of the castle and were able to break it

open. The vault was loaded with artwork, old gold coins, precious jewelry

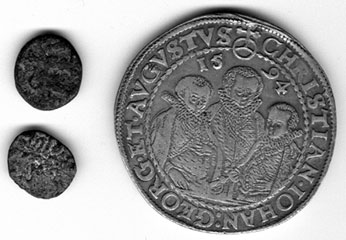

and other valuables, which the soldiers looted.

One of the men saw me and

showed me a box of very old, gold Spanish coins. I told him that taking the

coins, or any of the other valuables, would be considered a war crime, and

that if he were caught he would be court-martialed. He gave me the box of

coins and I immediately took it to the company commander and explained what

had happened.

The commander called an

assembly of the entire company, which seldom happened in combat. He

explained to the men that we were guests of the very lovely, sophisticated

woman at his side, as she was the current owner of the castle. He said that

all the valuables belonged to her, and asked that they be returned to a

specified room in the castle. He also told them if they didn’t return

everything by sunrise the next morning and were later found with any of the

valuables in their possession, they would be court-martialed and sent to

prison.

The next day he introduced

me to the woman, who thanked me for telling the commander about the looting.

She said that, to the best of her knowledge, everything had been returned.

She also gave me a few coins as a souvenir. I wondered at the time why the

Germans had not taken any of her possessions, and I suspected she may have

been a German collaborator.

|

|

I Received Coins as a Souvenir |

One of my missions took me

to Hamburg, Germany, a port from which my father had caught a ship to the

United States after fleeing from Russia in 1914. My target for this mission

was a high-ranking Gestapo officer.

In some of my missions I

would have been at risk to use anything that made noise while eliminating

the target. In situations like those, I used the hand-to-hand methods I had

been taught. I was more comfortable with some of these methods than others,

but I did whatever it took to get the mission completed successfully.

In this case I found my

target in the men’s room of a beer hall. I had followed him in and,

fortunately, we were the only two in the room. I was standing at the urinal,

which was the old floor style, when the officer came up behind me. He made

the mistake of tapping my shoulder. Perhaps he just wanted a cigarette, or

to know what outfit I was with, since I had no identifying patches on my

arm. But I wasn’t taking any chances, and besides, I figured it was as good

a time as any to carry out my orders. I grabbed his arm and threw him over

my shoulder, crushing his head against the urinal wall. And then, to be

certain, I broke his neck.

As I was dragging him into

one of the stalls, I heard the door to the men’s room opening and saw a

soldier entering. I immediately yelled at him to please help me, and said

that Herr Schultz (not his real name) had passed out. As soon as he got

close enough, he too ended up with a broken neck. He was a clean-cut,

good-looking young man, and I really hated to eliminate him. I can, at

times, still see his face. I put each man into a stall, dropping his

trousers and sitting him on a toilet. I locked each stall and slid out under

the door. I was thankful no one else had come in, since there were only two

stalls.

While trying to make my way

back to American lines, I found myself marching along with German

infantrymen. We were strafed by three American P47s, which the Germans

called Jabos. Of course, at this time I was still wearing the uniform of an

SS Panzer unit infantryman. This was one of the most terrifying things that

happened to me, including being shot at by German 88s on Utah beach. There

was no place I could hide, and the 50 caliber bullets were tearing into the

ground and into the German soldiers on all sides. My luck held and I wasn’t

hit, but there were dead bodies and soldiers yelling for help all around me.

I helped bandage as many of the wounded Germans as I could, and then took

advantage of the situation to lose the outfit.

I had walked around four

hours when I came across a field that had received heavy American shelling.

There were forty dead German soldiers, two dead American soldiers, who must

have been prisoners, and a number of dead horses. All had been killed by the

concentrated artillery fire. The stench of death was almost suffocating.

After inspecting the bodies of the American soldiers to make certain they

weren't booby-trapped, I took some of the extra clothing they carried in

their backpacks, along with the jacket of the man closest to my size, and

changed uniforms.

As I continued on through

another field, I thought I heard someone approaching. In trying to conceal

myself, I found a plane which had been cleverly camouflaged. Upon further

investigation, I found thirteen more planes, also well camouflaged. They

were German jet planes, although until I saw their cockpits, I thought they

were German buzz bombs.

I went back to the field

with the dead German bodies and collected eighteen “potato mashers,” or

German hand grenades. I then went back to the field where the planes were

located and blew them up.

Because I happened to be in

the right area at the right time, I was asked to rescue someone from

Buchenwald, a concentration camp in Germany. I was to make my way to a point

on the outer perimeter of the camp, making certain to eliminate the camp

guards patrolling the area without alerting the other guards.

When I arrived, the man I

was supposed to meet had already made his way, with the help of prisoners

within the camp and a German camp guard, to a designated spot outside the

camp walls. The escapee was in a German uniform that had evidently been

supplied to him by the camp guard. I learned at my debriefing that the camp

guard had been paid off with American dollars and promised some type of

position, along with immunity, once the war ended.

The escapee and I were

together for four days before I got him to the pick-up point on the coast

where I had been instructed to take him. I had been told not to ask him his

name or occupation, why he had been put into a Nazi concentration camp, or

how he’d broken out of the camp. And during the four days we were together,

he never offered to tell me.

I was near the city of

Remagen, Germany in early March of 1945, trying to get back to American

lines, when I received an order that was relayed to me by someone in the

German underground. I was to try to prevent the Germans from blowing up the

bridge over the Rhine at Remagen so that our tanks could cross. I managed to

join a conscripted Polish unit that was fighting and working under German

military supervision. They had been assigned to guard the bridge and, if

necessary, to blow it up to prevent the American forces from crossing over

it. I spoke no Polish and I wasn’t sure how the Poles would react to my

being there. But I didn’t speak to them and they didn’t speak to me, and we

got along fine.

The American artillery and

tanks were shelling the German side of the bridge, attempting to eliminate

their fire-power, so they could cross over and move on to Berlin. Because

their limited manpower was taking a heavy toll from the American shelling,

the Germans were ordered to destroy the bridge. They ordered the Poles to

move into an encampment built under the end of the bridge, and I went with

them. We were all huddled in a group near the batteries that were supposed

to detonate the explosives. The Germans had done a good job of protecting

the wiring and the terminals to which they were connected by running the

wiring in metal conduit. I hadn’t received much training with regard to

explosives, but I did everything I could do to loosen the conduit

connections and to separate the wires from the terminals, and then I got the

hell out of there.

Whether what I did helped

keep the bridge from being blown up, or whether it was something someone

else had done, I’ll probably never know. But I do know the bridge was there

the next day, and our tanks and trucks were able to cross over to the German

side.

On April 16th, 1945, I was

slightly wounded in my left leg by American artillery fire while making my

way back to our lines. Believing that I was in a fairly safe area, and so

not taking the precautions I normally did, I was captured by a German

headquarters field artillery unit. It was near the end of the war, and they

knew it. I had little trouble convincing them that they would all be better

off surrendering and allowing me to bring them back to the American side.

They abandoned their artillery, dropped their guns by the side of the road,

and with a white flag of truce, we all proceeded to walk back toward

American lines. When we got there I told an infantryman to get his

lieutenant and tell him that there were 180 prisoners there in need of

someone to take charge of them.

When the lieutenant arrived

and saw all those German prisoners, he immediately left to get his captain.

When the two officers came back, I told them that I didn’t like the idea of

being captured, so I had talked the officers in command of the German

soldiers into letting me capture them. The captain just shook his head, and

the only thing he said was, “Good work!” I had taken a Luger from the German

officer in charge of that unit, and I still have that gun. After the war

ended, I received a Purple Heart for the wound I received on April 16th,

even though it was from American fire.

In late April or early May

of 1945, I was sent to a town in the foothills of the Alps just in time to

see the liberation of the Dachau work camp. I saw Germans of all ages, men

and women, cleaning up the camp and burying the dead. The sight of the

prisoners, so thin you could see the outline of their bones, dressed in

their striped pajamas, and looking like dogs that had been continuously

beaten into submission, was enough to make anyone sick. I later learned that

General Taylor had been so incensed at what he found in the camp that he

ordered all Germans between the ages of 14 and 80 in the nearby town to

clean up the camp and bury the dead. They all claimed they had not known the

camp existed, even though the town was only three-quarters of a mile from

the camp.

Part Seven

Part Seven

|