|

Part Seven

The day the war in Europe

ended, I was called into headquarters and told my brother’s plane had been

shot down over the southern part of Japan, while on what was to be his last

mission. My brother, Lt. Harley T. Hammerman, was a bombardier/navigator on

a B29 bomber, and part of its eleven-man crew. To the best of my knowledge,

his plane was the last US plane of the war to be downed. The gunners on his

plane had shot down a two-man Japanese fighter plane. The two men in the

Japanese plane, knowing they were going down, were able to guide their plane

into the B29, knocking the right wing off. Both planes crashed onto a farm

on Mount Hachimen.

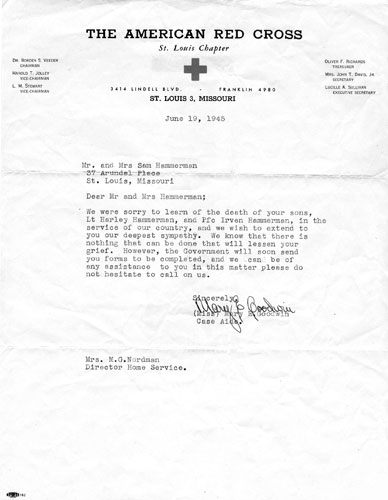

On June 19, 1945, the

American Red Cross sent a letter to my parents in St. Louis that said, “We

were sorry to learn of the death of your sons, Lt. Harley Hammerman, and

Pfc. Irven Hammerman, in the service of our country, and we wish to extend

to you our deepest sympathy.” Of course the report of my death was a

terrible mistake, but my family didn’t realize this until they remembered

they had received mail from me that was dated after the date of my death as

stated by the Red Cross. Previous to receiving this letter, my parents had

received official notice from the Air Force about the death of my brother.

It was tragic enough to have lost one loved one, but to believe that both of

their sons had been killed was devastating to my parents.

|

|

Letter from Red Cross dated June 19, 1945 |

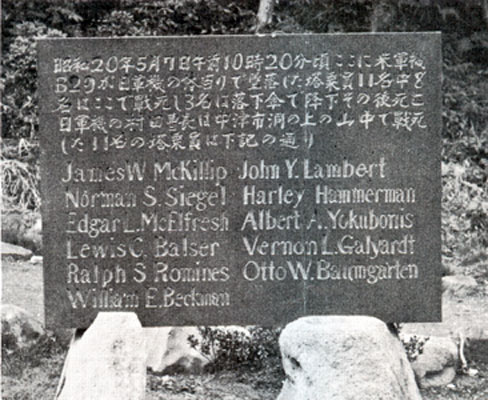

The owner of the farm where

my brother’s plane had crashed, with the help of his peace-loving Japanese

neighbors, decided to build a beautiful monument dedicated to peace and to

the thirteen brave men whose lives ended there. Army Sergeant Howard D.

Standefer represented the U.S. Government at the dedication of the monument

in 1971. The monument displays a picture and the names of each of the men on

the B29 and the two men in the Japanese plane.

|

|

Mount Hachimen Peace Monument |

The war in Europe was over,

and the Allied command needed to establish some kind of authority as quickly

as possible in the occupied part of the continent. I was put in charge of

sixteen small towns, and I had my headquarters in Dollwang. Most of my

duties consisted of going from town to town to see if there was any shortage

of medical supplies. A woman who lived in one of the towns and knew both the

people and the area was put on the army payroll and accompanied me.

While I was in this area,

two men who spoke with British accents approached me. Both were in British

combat uniforms and indicated that they were working with British

intelligence. They evidently had heard about my missions from someone at

Eisenhower’s headquarters. They wanted to know if I would be interested in

working for the Haganah, the underground Jewish military organization in

Palestine, which was later to become the army of Israel. I thanked them for

thinking that I could be of service, but told them I had lost a brother in

the Pacific and did not want my parents to have to worry about losing

another son.

In the summer of 1945 I was

shipped back to the states, landing in New York to the cheers of thousands

of people—many of whom were hoping to see their loved ones. We went by truck

to Fort Dix, New Jersey, where I was given new dress uniforms. I showered,

went to the enlisted men’s mess hall, and had my choice of entrees (I took a

thick, juicy steak), plus all kinds of side dishes and desserts. While on

leave, the war in Japan ended with the dropping of two atomic bombs.

Certain warnings were given

to me at the time of my separation from the army. I had to promise that I

would never reveal what I had done during the war or the names or locations

of any of my targets for a period of at least 35 years. I was informed that

this was for my safety as well as the safety of my family.

I know some may think the

things I did on my missions were exciting and maybe even a little heroic. I

have always felt, though, that the real heroes of the war in Europe—and the

same is true of the war in the Pacific—were the rangers and infantry. These

were the men who climbed the cliffs at Omaha Beach and knocked out the

pillboxes in the face of heavy German fire. They fought from hedgerow to

hedgerow in Normandy while the Germans occupied the adjacent fields. They

fought to take one town after another, fighting from one building to the

next. They fought to cross river after river and take hill after hill. In

most cases, the Germans and the Japanese knew when the Allied infantry was

coming, and they were prepared to deal with them. I had an advantage in that

the Germans never knew I existed.

I now realized that even if

there were surviving records of what I did during the war, I would never see

them. And the same, in all likelihood, is true of anyone who was involved in

espionage during World War II. The OSS (now the CIA) and G2 (army

intelligence) would never make this information available to me or to anyone

else.

It has always been painful

for me, even after all my years of mandated silence, to recall what I did in

the name of war—even though I know I completed these missions for my

country, and against a vicious enemy. The reason I have found it very

difficult to relate the details of these missions is because this is

certainly not the way I would want to be remembered. I just want to be

remembered as a good person and, most of all, a peace loving man, who very

much loved his wife, his children and his grandchildren. |