|

Part One

I was a gymnast in high

school and college. I also studied French and German for three years each,

and took Judo lessons while attending Washington University in St. Louis. I

took other subjects as well, since I was a chemistry major, and while all

these subjects would play an important part in my overall life, it was the

Judo, French and German that seemed to be the determining factors in my

future in the military.

|

|

|

|

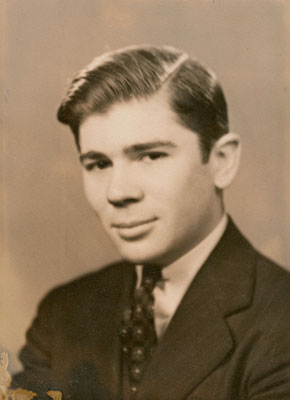

Year Book Picture, June 1938 |

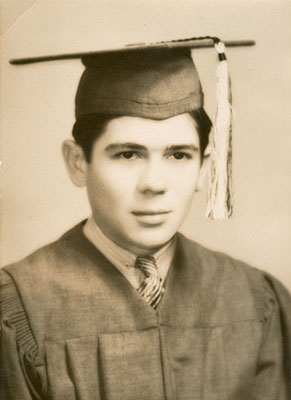

High School Graduation, June 1938 |

In the summer of 1940, after

going to almost every company in St. Louis that had some type of chemistry

lab, I landed a summer job at the American Car and Foundry Company. In those

days, many companies wouldn’t hire you if you were of a certain religion.

There were even large companies that would hire you only if you practiced

the religion set forth by their company guidelines, and this information was

requested on their job applications. However, none of this information was

requested on the American Car and Foundry employment application.

Just before it was time to

return to Washington University for the fall semester of what was to be my

final year, another company hired my boss, the chief chemist in charge of

the qualitative, quantitative lab at ACF. Before he left, he recommended me

over two other assistants, both of whom had been there for several years, to

take over his position. Needless to say, I was overwhelmed to know that he

thought I had done such a good job as to warrant his recommendation. As a

result, I got the position of chief chemist. My salary went from $20 a week

to $185 a month and, believe it or not, that was considered to be pretty

good. Getting the position meant I could not go back to Washington U. during

the day, but I did continue my studies at night school to try to finish the

hours I needed to graduate.

My work at ACF primarily

consisted in the qualitative and quantitative control of certain chemicals

that were used in metals to improve the quality of freight car wheels and

brake shoes. It really was not a very exciting job, even with the promotion,

but the work was considered to be vital to the war effort because of the big

part the railroads played in the shipment of war materials.

As a result of my position,

I was permanently deferred from the draft. However, as I would pass people

on the street I would feel that they were staring at me and thinking, “What

could be wrong with him?” since I was not in uniform and looked the picture

of health. In fact, some individuals who, I am certain, had loved ones in

the service, asked me if I was 4F and if so, what was wrong with me. Because

of this and after having been at ACF for only about eighteen months, I told

my employer that I wanted to leave to go into the army, and that I was

certain that I could train one of the other men to handle the position. I

requested they send a letter to the Draft Board stating this so I could

enter the military service. I felt good about my decision, especially since

my younger brother, Harley, was already serving in the army air force.

I reported to the Jefferson

Barracks Induction Center, about ten miles south of St. Louis. After I

passed the army intelligence and physical tests, I, along with the other

draftees, reported to the supply room. This was manned by four soldiers—men

in their thirties who, in civilian life, had been entertainers, comics and

singers in St. Louis night clubs like the Peppermint Lounge, where Davy

“Nose” Bold was the headliner. These entertainers, now soldiers, would take

a quick look at you, shout out their guess as to your shirt, pants and shoe

sizes, and then throw the items at you, all the time telling jokes and

singing parodies about life in the army. All in all, they made the induction

process easier and helped take our minds off of the family and friends we

were leaving behind, as well as that part of our life which lay ahead.

I received a very high score

on the army intelligence test, and, as a result, they kept me at Jefferson

Barracks for six weeks while they decided what position I would best be

suited for. During that period, I operated the blood and urinalysis lab. I

guess they thought this was as close as they could get to what a chemist was

trained to do. During my stay at Jefferson Barracks, I got a good look at

the different types of people who made up the eastern half of Missouri. They

were young men who had come from the very wealthy suburbs in St. Louis

County, the city of St. Louis and other cities in the eastern half of

Missouri. Some of the new recruits were from the middle and lower income

families that were just beginning to emerge from the depression of the

Thirties. And some of them, referred to by both the commissioned and

non-commissioned officers as “hillbillies,” were brought up on the farms in

southeast Missouri and in the beautiful Ozark mountains.

All of these men had to come

through the urinalysis lab. Many of them, even though they were just

eighteen, went on a drinking binge the night before they had to report for

induction and, as a result, had to be kept over due to the high level of

albumin that showed up in their urine sample. Some, who I really believe

didn’t know any better and did not have to urinate at the time, would ask

one of their buddies to fill their sample bottle. Some, who did not want any

part of the United States Army and just wanted to be sent back home, would

do anything from trying to “flunk” their eye and hearing tests, to putting

something in their urine sample to ruin that test. But the majority of the

men, really eighteen and nineteen year old boys, were good and clean cut and

went through thirteen weeks of basic training at the various army camps

across the country before they were sent overseas. It was these men from

Missouri as well as those like them from the other states and the U.S. owned

territories that made up the backbone of “Uncle Sam’s” fighting forces

around the world.

At the end of my first week

at Jefferson Barracks, I was told to report for a psychological evaluation.

While the psychiatrist was evaluating me, we were being pestered by flies. I

finally reached up toward one that was buzzing around my head and caught it

in my hand. The psychiatrist asked if I could do that every time and I said

that I could. He made some notes and told me to report back to the blood and

urinalysis lab, where I remained for another five weeks.

From Jefferson Barracks I

was sent, along with fourteen other men, to Camp Barkley, near Abilene,

Texas. I was made an acting corporal in charge of the fourteen men for the

trip. We were loaded into the back of an army truck and driven to Union

Station in downtown St. Louis, which was unbelievably jammed with people.

There must have been thirty gates, with people, both military and civilian,

arriving or leaving at every gate. We boarded the train to Abilene, Texas

and I had fifteen tickets, all of which called for sleeper cars. However,

the conductor told us that there were no sleeper cars available and that we

would have to make out the best we could in the coach cars. This was my

first trip on a train, or, for that matter, any kind of public

transportation other than a city streetcar, and it was a very crowded train

at that. Because of my lack of knowledge with regard to traveling, and

because I didn’t know enough to assert the rights of the other men as well

as my own, we ended up sleeping in the aisles. Only later did I find out

that the conductor, making an educated guess that the fifteen of us had

never been within a few miles of our respective homes, much less traveled on

a train, had sold our sleeper cars to civilians and pocketed the money.

After we got to Camp Barkley and talked to other new draftees, we found that

they had similar experiences and that we had been “taken.” At a later date I

read that this situation had been corrected and that those involved were

prosecuted.

Camp Barclay was located

about fifteen to twenty miles outside of Abilene, Texas in what seemed to me

to be a hot desert area, except that, instead of sand, the soil was red

clay. The clay must have dissolved in the water because if you washed

anything white, your clothing ended up with a nice reddish tint. The camp

seemed to cover an area larger than many cities. There was row after row of

barracks, and a mess hall that fed hundreds of soldiers, which was where we

all took our turn at KP Duty. This entailed helping to prepare the meals

(which might include peeling a room full of potatoes), serving the food,

cleaning the kitchen and mess hall, or anything else the mess sergeant

wanted you to do. There were parade grounds that seemed to go on forever,

firing ranges and obstacle courses. The one thing we took an immediate

liking to was a huge PX—a Post Exchange, where you could buy just about

anything if you had the money.

Basic training started the

day we got to camp. There was a captain in charge of our company, and a 2nd

lieutenant, a sergeant and a corporal in charge of each of the four

platoons. The corporal in my platoon was a six foot three inch man who

seemed to be all legs. For some reason or other he singled me out in one of

our first formations. He announced the next day’s schedule, which included a

short two-mile hike, and said, “Hammerman, I’m going to walk your legs off.”

I was amazed at how hard

this hike was on most of the recruits. But they were not used to running

four miles at 6:00AM every morning around the track at Washington

University, followed by an hour-and-a-half work out in the gym before going

to their first class. To add to the initial discomfort, that part of Texas

reached upwards of a hundred degrees in the daytime but could, thankfully,

drop about thirty to fifty degrees at night. However, after thirteen weeks

of training, these same men, who could barely make the first two mile hike,

could do an eight mile speed march, with full pack, in two hours and then be

ready for anything that might come along next, especially if it were a five

hour pass into town.

I remember on one of our

earlier hikes, on a particularly hot day when most of us were just about out

of water in our canteens, the corporal had us fall out for a five-minute

rest period and we found ourselves right next to a field of beautiful, ripe

watermelons. We broke open a number of them and dug out the juicy, red melon

with our hands and, in this way, quenched our thirst. We had just about had

our fill when the farmer who owned the field appeared. He was very nice but

said he was going to have to charge us for the melons. He charged us only

ten cents for each melon, which everyone was more than happy to pay. In any

event, the corporal, who overall did a great job of whipping all of us into

shape, was pretty much at my side through out all my basic training and I

had the feeling that he was reporting to someone on everything I did.

While at Camp Barkley, I met

Sergeant Burns. I will never forget him or his name, primarily because he

spent part of his time selling his good will to the recruits by borrowing

money from them in the amounts of twenty, thirty or forty dollars. He

approached me on a “loan” of forty dollars. I agreed to lend him that

amount, providing he signed an IOU. After a little talk about trust, he

reluctantly signed the note and I gave him the forty dollars. When it came

time for all of us to ship out, I reminded him of the loan. I told him to

pay up or I was going to the captain. After several days he decided that it

was in his best interest to pay me, but I knew that he did not pay any of

the other men. About two months later, I read in the army newspaper, “The

Stars & Stripes,” that Sergeant Burns had been court-martialed for these

activities and would be serving time.

After Camp Barkley I was

transferred to Fort Gordon Johnson, Florida, where I was attached to the 4th

Infantry Division Headquarters Medical Detachment and assigned to Company C,

42nd Field Artillery Battalion. We all went through some very strenuous

amphibious training. One of the first things the non-coms in charge of

training did was to tell about ten of us, who were in full combat dress with

fifty-pound packs, that they were going to drop us off about fifty yards

from the end of the pier. We were to make our way back to the pier with the

fifty-pound packs. Of course we all made it back and only one of us lost his

pack. It was off of this same pier that several of the soldiers, who were on

KP duty, caught red snappers, hauling them in one after another just as fast

as they could put new bait on their hooks, until they had enough fish to

feed the entire company.

In addition to the ongoing

physical training, we made various assault landings from all kinds of

landing craft on small, uninhabited islands. It was rumored that, during one

of these missions, a German sub torpedoed one of our troop ships. If that

did, indeed, happen, it was not at the time our outfit was there, and I

never came across any article relating the incident in any of the civilian

or army newspapers. I believe that every group going through the training

was told this to impress upon them the seriousness of the training they were

going through.

Part of Camp Gordon Johnston

encompassed the Everglades, and the barracks must have been built on wood or

steel piers that had been driven into the ground below the water so they

would be able to bear the weight of the barracks, soldiers and all of their

possessions. In our barracks you could see the water through the wide cracks

in the slat floor. We all used a lot of mosquito repellent, and at the time

of our training I thought, “What a hell hole.” However, in later years, when

I had occasion to drive through the Everglades in my air-conditioned car, I

marveled at the beauty of the trees, shrubbery, and wildlife that live

there.

Part Two

Part Two

|