|

Part Two

From the Everglades, I went

to England, still with the medical unit attached to Headquarters of the 4th

Infantry Division. I was instructed to give my family and friends the

following as my permanent army mailing address:

Headquarters Medical

Unit, Company C

42nd Field Artillery Battalion, 4th Division

I was told that all mail

would either be saved or forwarded to me, if possible. I was also told by

the battalion commanding officer that I might be going through special

training in the near future but, for the time being, I was to remain and

train with the 42nd. He told me he had no knowledge of what might be

involved in this training, and instructed me to say nothing about it.

|

|

|

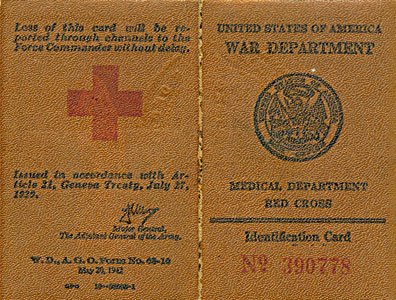

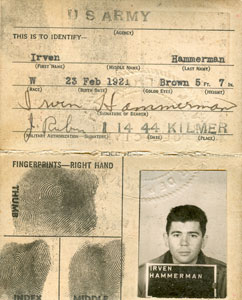

My Identification

Card |

The entire division, about

eighteen thousand men, went overseas on a luxury liner that had been

converted into a troop ship. While aboard ship, we ate, exercised and slept

in shifts. We slept in hammocks stacked five high, with no more than

eighteen inches between hammocks. The space between the rows was so narrow

that it was almost impossible for us to pass each other. Under the bottom

hammock, which was about thirty inches above the deck (twenty inches when

someone was in the lower bunk), were piled our five duffel bags, one for

each soldier, containing all of our clothing, toiletries and other worldly

possessions.

The trip across was very

rough and many of the men got seasick, while others looked like they really

enjoyed the sea and probably should have been in the navy. The convoy, which

extended as far as the eye could see, consisted of troop ships, supply ships

and protective naval vessels. When we were within a hundred miles of the

English coast, our convoy was attacked by German subs. We lost several ships

and I don’t know how many men.

After fourteen days, we

docked in London. At night, in a pouring rain, we boarded a train—each man

carrying his duffel bag over his shoulder—and after six or seven hours we

reached Honiton, a town located in the county of Devon in the southwestern

part of England, just fourteen miles east of Exeter. We left the train and

were loaded onto army “six by six” trucks and, after a rather short ride, we

reached our destination—a farm about a half-mile outside of the town.

There were rows of Quonset

huts, which had been recently erected, and each hut contained a row of six

showers, six toilets, a potbelly stove and enough bunks for thirty

soldiers—the number of men in a platoon, or two squads. This was to be the

42nd’s home while in England, and for as long as we were there, the rain

never let up.

What I remember most about

Honiton were the people, who were warm, friendly and very appreciative of

our being there, and my introduction to fish-and-chips. Soldiers in training

are always hungry, and so after evening chow, and sometimes after several

hours of additional training, two men would either go over the fence

enclosing the camp, or would proceed through the main gates where guards

were posted in order to bring back as much fish-and-chips as they could

carry. The payoff to the guards for letting the two men go back and forth

through the main gates without reporting them was a portion of the

fish-and-chips. I am certain the officers knew what was going on.

While training in Honiton,

our commanding officer decided we would undergo a surprise gas attack just

to see how we would react. Everyone put on his gas mask except for one

soldier, whose name was Harvey Wolpen. At first he held his breath while

trying to locate his mask. Finally, no longer able to hold his breath and

thinking he was dying, he found his mask, although he had removed the

canister that made the thing work some time ago to make a convenient

carrying case for his candy. He emptied out all the candy, put the empty

facemask over his head and proceeded to take deep breaths. Everyone was

laughing and told him that, if it had been a real gas attack, he would have

been dead minutes ago. Not too many months later, and only two weeks after D

Day, a sniper shot and killed Harvey while he was crossing a field

surrounded by hedgerows in Normandy.

It was in Honiton, while

shopping during some of my free time, that I purchased two small, framed

etchings. I knew nothing about art, but the elderly gentleman in the shop

who sold them to me assured me they were something my parents back home

would appreciate and that they would only increase in value. When I got

married my parents gave them back to me, and even though we have moved more

than a few times, we have always had them hanging in our home.

It was also in Honiton that

we underwent our first air raid. It started one night around 11PM. We were

all very frightened and, as previously instructed, dashed outside in

whatever we happened to be wearing at the time. Most of us were already in

bed, and since most of us slept in our underwear, we covered ourselves with

our rain capes and plopped ourselves down in the protective trenches which

others had already dug around the perimeter of each of the Quonset huts. Of

course the trenches were all muddy from the seemingly never-ending rain. The

permanent personnel at the camp had a good laugh, since the bombs fell at

least a mile away, and we all had to shower before returning to our bunks.

After that, when there was an air raid, the bombs had to fall very close

before we would even think about entering the trenches.

While in Honiton, I stopped

at one of the churches in town and asked the minister if he knew of a Jewish

family with whom I could spend the Passover holiday. He told me of a family

by the name of Samuels, who lived in Exeter, “just a short train ride away.”

He said he would call the Samuels to make all the arrangements, and that I

should check back with him in a few days. This I did and he indicated that

the Samuels would be delighted to have me as their guest for dinner on the

first night of Passover.

I wanted to bring the family

something, and in those days cigarettes were almost impossible for civilians

to obtain. Most people were not aware then, as we are now, of the health

problems that smoking could cause. Since I had never smoked and had been

accumulating my monthly cigarette rations, I brought them several cartons of

cigarettes, for which they were very thankful. I remember Mrs. Samuels

opening a pack of cigarettes into a tray and then asking that we all be

seated for dinner.

While they really didn’t

have a Seder, as they were very Reform, I still enjoyed and will never

forget that dinner. It consisted of English rare roast beef with various

side dishes, like small potatoes that tasted like they had been cooked in

the gravy of the roast beef, and fresh green peas that they had picked from

their vegetable garden. They didn’t have matzos, but they also did not serve

bread in observance of the Passover holiday. This was my first home-cooked

meal in about six months and it was really a great treat for me.

When the meal was over they

served after-dinner drinks, and Mrs. Samuels offered me a cigarette. I told

her that I didn’t smoke, and she turned to offer one to her daughter,

Pamela, telling her she should take one because, “they are good for your

nerves and will calm you down.” I found out that Mr. Samuels owned a picture

frame factory, and he told me how fortunate they were that it was never the

target of any of the German bombings.

I was invited back to visit

the Samuels several times, and Pamela showed me around the city of Exeter.

We walked along a two-lane road until we got to the main part of town, and

we did some shopping in the business district. On another visit, we took a

train ride to a beach in Torquay which, in peacetime, was a famous resort

area on the English Channel. Years later, while on a trip to London with my

wife, I tried to find the Samuels, but had no luck.

Part Three

Part Three

|